Art Alongside Capitalism: The Development of Graphic Design and Commercial Art in Alphonse Mucha

Mucha and his lithographs are considered among the earliest examples of modern graphic design. Graphic design is a product of capitalism, made necessary by the growing competition among businesses in similar fields, seeking to make themselves stand out to the consumers. Capitalism, as a whole, can coexist alongside art, and, similar to the process of the free market, has improved art overall through competition and the free trade of ideas.

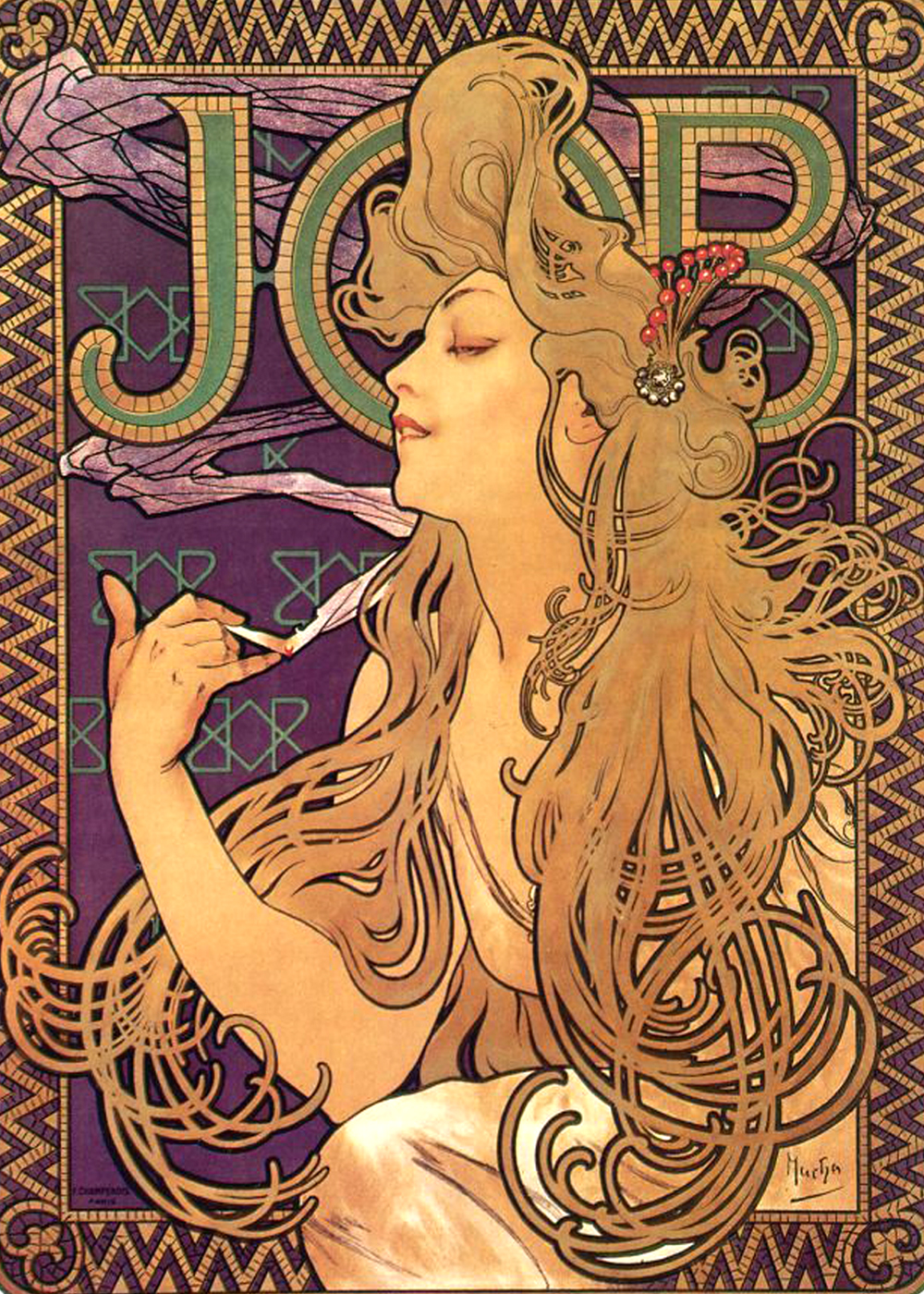

I will be focusing my thesis around one of Mucha’s more famous commercial works; a commission piece for JOB cigarette papers, completed in 1898:

This piece, while ornate and almost ethereal in its beauty, nonetheless may remind the viewer of similar compositions found in modern cigarette advertisements, or even any advertisements at all: the image of a beautiful woman, pleased beyond reason at the feeling of using whatever product or consumable is being sold. The colors are bright and inviting, and match the cigarette well. While JOB is central in the piece, it’s tertiary to the main attraction: the woman and her cigarette.

But the appearance of the piece is almost secondary. The primary draw to this piece, historically, derives from the oft-forgotten early history of commercial art. When most laymen think of early 20th century art, they envision the fine artists, whose works are more self-expression than formal, commercial, or marketable. In my mind, I see a split between the two worlds: the fine arts, which have no doubt brought the world much joy and meaning, and the commercial arts, which have given the modern world structure and a beauty all its own.

Mucha began his professional career in the late 1800s, stretching into the 20th century with the growth of the Art Nouveau movement, marked by a drive to explore the beauty of nature beyond the modernist world many artists found springing up around them. In contrast to the iconoclastic view of modern life by other, later art movements, Art Nouveau sought to celebrate nature amidst the urban world. Mucha appeared in bustling metropolitan cafes, on the exteriors of theatres and opera houses, in parlors and boutiques, reminding consumers of the wonder of nature and the human body. To some, it may seem hypocritical to advertise modern services alongside classical tapestries of nature’s beauty. But it’s worth bearing in mind the value of the world we came from, even as we distance ourselves from it.

My greatest hesitation in critiquing modern art has always been the distinction between art made for the self and art made for society. Commercial art, by nature, must almost always appeal to society in some way, as being sold and consumed is its objective. To some, this may seem stifling, but to others it presents an opportunity to work within the confines offered, as one might solve a puzzle. According to Richard Christopherson, “the notion that works of art are the result of individual genius is a widespread belief in Western culture...it ignores the very significant role played by the institutional structure in which works of art are created, evaluated, distributed, and finally absorbed into the cultural life of society.”¹

Design and commercial art, therefore, serves society, and exists to be presented to a broader audience for digestion and increased understanding. As Marilyn Rueschmeyer notes of the distinction between art under both communism and capitalism, “art and artists had become more and more emancipated from particular patrons and oriented to the market. In the process, autonomy for individual expression increased greatly, while innovation and experimentation became norms that dominated critical discourse as well as the upper-end marketplace.”²

This is a far cry from the vision some Marxist scholars present of the art world’s development under capitalism, in that it has only ever been a hindrance to true expression and artistic exploration, due to the need to play “dancing monkey” for the shadowy, unnamed upper echelons of capitalist society.

Fine art, on the other hand, lacks this limitation, and so has eschewed competition and high quality in exchange for a desperate scramble for uniqueness and flavor. In some ways, it is a puzzle which, rather than being solved, is simply thrown out and deemed too limiting.

In contrast to capitalism and the artists operating within it, the Soviet Union brought many artists to bear as well. However, these artists found themselves even more stifled than they may have considered themselves under capitalism, as the state demanded secularity and triumphant propaganda as the only use for their work, which paradoxically cannot exist alongside the socialist realism also demanded of artists at the time. Paul Sjeklocha: “The ecclesiastical state was able to define the deity, for a time at least, to the satisfaction of the artist. But the state does not require of the socialist realist a definition of man, it requires a depiction of a proletarian victory, a reality which is guaranteed by Marxist ideology but which remains an abstraction.”³

In essence, capitalism offers neither promises of victory nor demands of subject matter by the state, and so therefore expects little of those operating within it save what they find is most marketable or fulfilling. There’s no dictator to grip art by the neck and wrangle it into a shape which best suits his regime. By commercializing art, society is allotted a far more democratic means of controlling the world around them, whether rich or poor, uneducated or elite.

This can be seen most potently in the Art Nouveau movement, a period marked by gorgeous illustrations and lithography, and an appreciation for one’s craftsmanship and materials. Its name marks the thoughts of the period: “new art”, heralding a total shift in the world. As society became more industrialized and urban, so too did art. In the organic, flowing forms of Art Nouveau, a modern artist might find some solace from the geometric bustle of their daily lives in the growing cities of France and Europe as a whole.⁴

Mucha’s focus on form, shape, texture, and ethereal beauty was highly sought after for commercial purposes across Europe, eventually finding its way to America, where it eventually morphed into modern graphic design, alongside other industry titans both preceding and following in his footsteps. Regardless of one’s political opinions, capitalism can and has existed in harmony with the art world, allowing artists to challenge themselves and grow beyond the scope of their own worldview, biases, and shortfalls. Just as technology and culture continues to evolve in the free market, so too does art.

Bibliography

1. Christopherson, Richard W. "Making Art With Machines:." Urban Life and Culture 3, no. 1 (1974): 3-34.

2. Rueschemeyer, Marilyn. "East German Art Before and After the Fall of Communism." Art and the State, 2005, 126-53.

3. Kovarsky, Vera, Paul Sjeklocha, and Igor Mead. "Unofficial Art in the Soviet Union." Russian Review 27, no. 3 (1968): 364.

4. Paret, Peter, Debora L. Silverman, and Maria Makela. "Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siecle France." The Art Bulletin 73, no. 2 (1991): 333.

I will be focusing my thesis around one of Mucha’s more famous commercial works; a commission piece for JOB cigarette papers, completed in 1898:

This piece, while ornate and almost ethereal in its beauty, nonetheless may remind the viewer of similar compositions found in modern cigarette advertisements, or even any advertisements at all: the image of a beautiful woman, pleased beyond reason at the feeling of using whatever product or consumable is being sold. The colors are bright and inviting, and match the cigarette well. While JOB is central in the piece, it’s tertiary to the main attraction: the woman and her cigarette.

But the appearance of the piece is almost secondary. The primary draw to this piece, historically, derives from the oft-forgotten early history of commercial art. When most laymen think of early 20th century art, they envision the fine artists, whose works are more self-expression than formal, commercial, or marketable. In my mind, I see a split between the two worlds: the fine arts, which have no doubt brought the world much joy and meaning, and the commercial arts, which have given the modern world structure and a beauty all its own.

Mucha began his professional career in the late 1800s, stretching into the 20th century with the growth of the Art Nouveau movement, marked by a drive to explore the beauty of nature beyond the modernist world many artists found springing up around them. In contrast to the iconoclastic view of modern life by other, later art movements, Art Nouveau sought to celebrate nature amidst the urban world. Mucha appeared in bustling metropolitan cafes, on the exteriors of theatres and opera houses, in parlors and boutiques, reminding consumers of the wonder of nature and the human body. To some, it may seem hypocritical to advertise modern services alongside classical tapestries of nature’s beauty. But it’s worth bearing in mind the value of the world we came from, even as we distance ourselves from it.

My greatest hesitation in critiquing modern art has always been the distinction between art made for the self and art made for society. Commercial art, by nature, must almost always appeal to society in some way, as being sold and consumed is its objective. To some, this may seem stifling, but to others it presents an opportunity to work within the confines offered, as one might solve a puzzle. According to Richard Christopherson, “the notion that works of art are the result of individual genius is a widespread belief in Western culture...it ignores the very significant role played by the institutional structure in which works of art are created, evaluated, distributed, and finally absorbed into the cultural life of society.”¹

Design and commercial art, therefore, serves society, and exists to be presented to a broader audience for digestion and increased understanding. As Marilyn Rueschmeyer notes of the distinction between art under both communism and capitalism, “art and artists had become more and more emancipated from particular patrons and oriented to the market. In the process, autonomy for individual expression increased greatly, while innovation and experimentation became norms that dominated critical discourse as well as the upper-end marketplace.”²

This is a far cry from the vision some Marxist scholars present of the art world’s development under capitalism, in that it has only ever been a hindrance to true expression and artistic exploration, due to the need to play “dancing monkey” for the shadowy, unnamed upper echelons of capitalist society.

Fine art, on the other hand, lacks this limitation, and so has eschewed competition and high quality in exchange for a desperate scramble for uniqueness and flavor. In some ways, it is a puzzle which, rather than being solved, is simply thrown out and deemed too limiting.

In contrast to capitalism and the artists operating within it, the Soviet Union brought many artists to bear as well. However, these artists found themselves even more stifled than they may have considered themselves under capitalism, as the state demanded secularity and triumphant propaganda as the only use for their work, which paradoxically cannot exist alongside the socialist realism also demanded of artists at the time. Paul Sjeklocha: “The ecclesiastical state was able to define the deity, for a time at least, to the satisfaction of the artist. But the state does not require of the socialist realist a definition of man, it requires a depiction of a proletarian victory, a reality which is guaranteed by Marxist ideology but which remains an abstraction.”³

In essence, capitalism offers neither promises of victory nor demands of subject matter by the state, and so therefore expects little of those operating within it save what they find is most marketable or fulfilling. There’s no dictator to grip art by the neck and wrangle it into a shape which best suits his regime. By commercializing art, society is allotted a far more democratic means of controlling the world around them, whether rich or poor, uneducated or elite.

This can be seen most potently in the Art Nouveau movement, a period marked by gorgeous illustrations and lithography, and an appreciation for one’s craftsmanship and materials. Its name marks the thoughts of the period: “new art”, heralding a total shift in the world. As society became more industrialized and urban, so too did art. In the organic, flowing forms of Art Nouveau, a modern artist might find some solace from the geometric bustle of their daily lives in the growing cities of France and Europe as a whole.⁴

Mucha’s focus on form, shape, texture, and ethereal beauty was highly sought after for commercial purposes across Europe, eventually finding its way to America, where it eventually morphed into modern graphic design, alongside other industry titans both preceding and following in his footsteps. Regardless of one’s political opinions, capitalism can and has existed in harmony with the art world, allowing artists to challenge themselves and grow beyond the scope of their own worldview, biases, and shortfalls. Just as technology and culture continues to evolve in the free market, so too does art.

Bibliography

1. Christopherson, Richard W. "Making Art With Machines:." Urban Life and Culture 3, no. 1 (1974): 3-34.

2. Rueschemeyer, Marilyn. "East German Art Before and After the Fall of Communism." Art and the State, 2005, 126-53.

3. Kovarsky, Vera, Paul Sjeklocha, and Igor Mead. "Unofficial Art in the Soviet Union." Russian Review 27, no. 3 (1968): 364.

4. Paret, Peter, Debora L. Silverman, and Maria Makela. "Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siecle France." The Art Bulletin 73, no. 2 (1991): 333.

Comments

Post a Comment